This week marks the 75th anniversary of the D-Day landings on 6 June 1944, the Allied invasion of France. Here, we tell the story of a CBA staffer, Bill McGowen, who took part in the campaign that ultimately led to the end of World War 2 in Europe with the defeat of Germany the following May.

Around 3,000 Australians were involved in the largest sea-borne invasion in history, most of them aircrew in the Royal Australian Air Force and the Royal Air Force who flew bombing, fighter and paratrooper/glider missions to support the D-Day landings in Normandy.

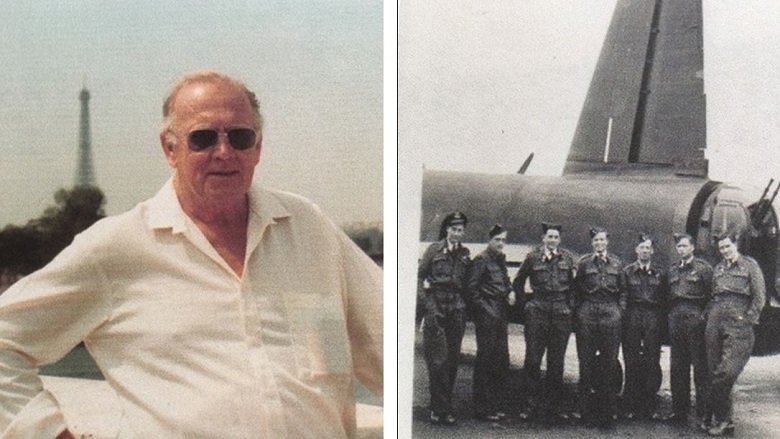

Among them was Flight Sergeant Bill McGowen, who three years earlier had left school to become a clerk at the CBA branch in Nowra in southern NSW before transferring to Carlton branch in south-western Sydney.

Bill had followed in the footsteps of his father, Ferdinand, a long-standing CBA employee who had fought at the Battle of the Somme in WW1, returning home at the war’s end to serve as the manager at Bega, Narrandera and Bexley branches in NSW.

Just 20 years of age, Bill was already a veteran of 14 bombing missions over France and Germany when he and his fellow crew members boarded their four-engine Lancaster heavy bomber of 467 Squadron at RAAF Waddington, located in the flat, isolated fields of Lincolnshire in eastern England, in the early hours of 6 June 1944.

Bill was the bomb-aimer, the most important member of the seven-strong crew after the pilot when the plane was over the target. It was a role for which he had trained long and hard and one which had taken him from Australia via Canada, Wales and England on training missions before his posting to Waddington.

Mission Impossible

Taking off at 2.30am, 467 squadron clawed for open sky among 1,200 allied aircraft, all converging on the Normandy coast and the hinterland around the five landing zones. The weather leading up to the invasion had been atrocious and the small window of opportunity to go ahead with it had only opened up a few hours beforehand.

But that was of little comfort for Bill and his mates flying thousands of feet above the invasion fleet. In his diary, written many years after the war, Bill recalled: “The weather was shocking, thick cloud all the way and we began to ice up badly.

“The ice was breaking off the wings and hitting the aircraft with bangs, also my compartment was thick with ice and I had no visibility at all. It would, under those conditions, be impossible to bomb. Tom, our pilot, decided to descend below cloud level into warmer air. At about 4000 feet we flew around for twenty minutes or so until the ice melted.”

It was then that the crew realised the momentous nature of the operation they were involved in. “Immediately we saw a sight that never will be seen again,” Bill wrote in his diary. “Hundreds and hundreds of ships in an area twenty miles long and seven miles wide. The invasion of Europe had started.”

The 14 bombers of 467 squadron had been tasked with knocking out the German coastal gun batteries at St-Pierre-du-Mont to support the American forces landing on what was known as Omaha beach.

By the time Bill’s Lancaster arrived over the bombing zone – much later than originally planned – there was no other Allied aircraft in the area. Mark, the plane’s navigator, plotted a course for the target and as it appeared the crew could see there was little bomb damage.

Bill takes up the story. “It was full daylight and it was a perfect bombing run. I could see a radar mast still standing and aimed for it. It was a perfect drop, the bombs forming a line running up to and through the radar installation. I was unable to assess the damage but Col, the rear gunner and Mark reported seeing the mast topple over. That was our contribution to D-Day.”

Luck on the day

Except the drama didn’t stop there. A history of the squadron’s war exploits baldly states all bombers returned to base at 7am with no losses. However, that could have turned out very different and with tragic circumstances if it had not been for the professionalism of those on board Bill’s plane, the ground crew at Waddington and a huge amount of luck.

After leaving St-Pierre-du-Mont, Bill noticed a light was still glowing on the bombing panel which meant that one bomb – a 1,000 pounder with easily enough explosive power to destroy the Lancaster – was stuck in the bomb bay.

“Jettison bars were activated, but no result,” recalled Bill in his diary. “Mark (the navigator) also tried to release it through an access panel in the body of the aircraft, but again no result. We opened the bomb doors again and flew out to sea away from the invasion force.

“Jinking all over the sky to get the dammed thing to drop did not work either. Now this was pretty hairy as we had to land with a bomb on board. Arriving back at the squadron 30 minutes late, we radioed the information to alert emergency services.

“We went into our usual landing pattern as carefully as possible. On landing there was a slight thump somewhere aft. The landing had finally released the bomb that was only retained by the bomb bay doors. Ground crew had to work gingerly to remove it safely.”

Postscript

Bill’s luck was to hold for another 12 missions until his 27th when his Lancaster was shot down over Revigny, close to French-Swiss border in the early hours of the 19th July 1944.

Two of the crew were killed, including his best mate, rear-gunner Col Allen, and two others were taken prisoner when they bailed out of the aircraft. After parachuting and landing alone, Bill was taken in by local people and then handed over to the French Resistance.

Meeting up with two of his surviving crewmates, the trio were eventually picked up by an advancing patrol of American soldiers and safely returned to England in September 1944. The news of Bill’s survival and rescue was relayed to his relieved CBA colleagues in the staff magazine, Bank Notes, that same month.

Promoted to Warrant Officer, Bill was subsequently posted home to Australia in 1945 and after being demobbed, resumed his career with the Commonwealth Bank, retiring as manager of Miranda branch in NSW in the mid-1980s.

Editor’s Note: Our thanks to Bill’s family, in particularly his nephew Paul Beale, an executive portfolio manager, IT services in Enterprise Services at Commonwealth Bank Square, for their help in and support of preparing this article.