The guns had been silent on the Western Front for five months and the Great Powers were edging closer to signing the Treaty of Versailles that would officially signal the end of World War One.

But while the death and destruction caused by war may have been at a close, an even worse killer – if that was thought possible - was sweeping through a devastated Europe and beyond.

The outbreak of what became known as “Spanish Flu” in 1917 quickly became a global influenza pandemic, estimated to have killed more than 50 million people over three years. No country was considered safe, with deaths recorded in South America, the US and Canada, India, Japan, South-East Asia, New Zealand and the Pacific Islands.

Australia was not immune despite strict quarantine policies. By the time the outbreak subsided at the end of 1919, 40 per cent of the domestic population had been infected and 15,000 people died.

CBA response

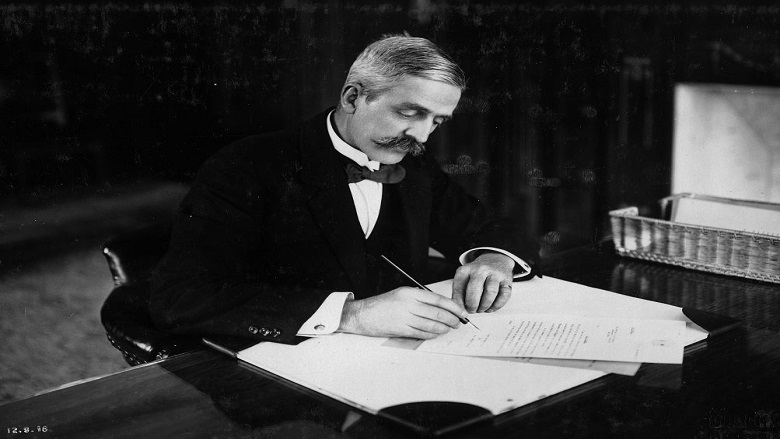

Denison Miller, the first governor of the Commonwealth Bank (pictured below), had witnessed the effects of the pandemic at first hand while on a tour of North America, the UK and the European battlefields in 1918. Writing at the time in Bank Notes, the group’s staff journal, he recounted visiting New York, Washington, London and Auckland, where the virus was killing thousands of people.

It was an experience that left its mark on the Governor. Following his return to Sydney – which involved a period in quarantine to ensure he was not infected with the flu – Miller was instrumental in appointing the bank’s first medical officer, in April 1919.

Career nurse

By all accounts, Sister Elizabeth Ellen Murrell was an indomitable woman with a reputation to match. A career nurse who had grown up in the Sydney suburb of Gladesville and spent her first years working at the Home for the Incurables in Ryde, she had seen her fair share of suffering by the time she joined the bank.

Appointed matron of a convalescent home at Eastwood in 1916, her life took a dramatic turn a year later when, at the age of 37, she followed in the footsteps of her younger sister, Emmeline, also a nurse, by joining the Australian Army Nursing Service.

They were among about 3,000 civilian nurses from Australia who volunteered for active service in the war. Elizabeth was posted to Salonika in Greece in June 1917, where she cared for sick and wounded British and allied soldiers suffering from dysentery, malaria and black water fever in harsh conditions during freezing winters and mosquito-ridden summers.

The medical staff were not immune from such sickness and 15 months after leaving Sydney, Sister Murrell was invalided home because of debilitating illness. Her sister Emmeline went through the same experience after serving in India, Egypt and England, returning to Australia in 1919.

Discharged from the service in November 1918 on the grounds of being medically unfit, Elizabeth resumed her civilian work at Randwick Hospital (now the Prince of Wales Hospital) before joining the bank.

The hospital touch

Her CBA clinic was a significant step up from the tents and huts that she had experienced near the front line in Greece. She was provided with a well-equipped sick bay at the recently opened head office in Pitt Street, where she cared for an increasingly large staff.

In an article for Bank Notes in November 1919, an unnamed writer noted: “In two rooms full of sunshine glistening white with the gleam of polished nickel and plate glass, conveying the hospital touch, Sister Murrell sits, white coiffed and white gowned, alert and ready to squelch the many maladies that beset the path of the toiling bank clerk.

“Sister says she finds us as ‘cases’ a very healthy, uninteresting lot from a professional standpoint and rightly so, she says. With the splendid building we are in and the healthy conditions generally, how could it be otherwise? And then Sister gets a reminiscent look in her eyes, the shadow of a sigh escapes her as she remembers the fine lives ‘gone west’ and from a sentence or two, you learn that men in hospital huts in frozen Salonika did not exactly live in the lap of luxury.”

Accolades and innovations

Honoured by Governor Miller during a speech in January 1920, Sister Murrell became an institution at the bank, introducing new innovations such as mid-day exercise sessions for the female staff, health talks and after-hours physical culture classes. She also helped to establish the bank’s hospital cot committee, part of the staff club that supported local communities.

Known as “Beth”, Sister Murrell stayed with the bank until retiring in June 1937. Her thank you presents at a farewell tea party held at the Pickwick Club in the Sydney CBD included a handbag from the staff and a wallet of notes from the bank’s deputy governor. She spent her retirement in Dee Why on Sydney’s Northern Beaches, dying in November 1970, aged 90.